A l’initiative du Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Fritz Volbach, conservateur de musée et professeur allemand actif dans la recherche des textiles archéologiques, un petit groupe de chercheurs se réunit à Lyon en 1954. La plupart d’entre eux se connaissaient déjà, car ils avaient correspondu à propos de textiles historiques depuis des années. Ils décidèrent alors de créer une association et lui donnèrent le nom de “Centre International d’Etude des Textiles Anciens” ; le Musée Historique des Tissus, ainsi nommé à l’époque, fut considéré comme l’endroit idéal pour accueillir cette nouvelle association. Les membres fondateurs étaient originaires d’Autriche (Dora Heinz), de France (Yolande Amic, Jacques Dupont, Félix Guicherd, Robert de Micheaux, Marie-Thérèse et Charles Picard, Monique Toury, Pierre Verlet), d’Allemagne (Ernst Kühnel, Sigrid Müller-Christensen, Wolfgang Fritz Volbach), d’Italie (Gian Piero Bognetti, Tito Broggi), d‘Espagne (Felipa Nino y Mas), de Suisse (Alfred Bühler, Verena Trudel), de Suède (Agnes Geijer) et des Etats-Unis (Claire and René Batigne, Calvin Hathaway, Margaret I. J. Rowe, Edith A. Standen). Travailler ensemble n’était pas une mince affaire à cette époque, car ils avaient tous vécu la Deuxième Guerre Mondiale, et l’antagonisme et la méfiance avaient prédominé pendant des siècles entre certains pays. Mais ces savants décidèrent de prendre un nouveau départ, de surmonter les préjugés anciens et de contribuer à une meilleure compréhension dans leur champ de recherche. Leur but était d’établir une langue définie avec précision pour décrire les éléments techniques et les structures des textiles tissés et de créer une documentation de textiles historiques qui devraient être décrits selon une liste détaillée de questions. Cette documentation, une collection de “dossiers de récensement” pour des textiles individuels, est conservée au musée des Tissus de Lyon où les chercheurs peuvent la consulter.

A l’initiative du Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Fritz Volbach, conservateur de musée et professeur allemand actif dans la recherche des textiles archéologiques, un petit groupe de chercheurs se réunit à Lyon en 1954. La plupart d’entre eux se connaissaient déjà, car ils avaient correspondu à propos de textiles historiques depuis des années. Ils décidèrent alors de créer une association et lui donnèrent le nom de “Centre International d’Etude des Textiles Anciens” ; le Musée Historique des Tissus, ainsi nommé à l’époque, fut considéré comme l’endroit idéal pour accueillir cette nouvelle association. Les membres fondateurs étaient originaires d’Autriche (Dora Heinz), de France (Yolande Amic, Jacques Dupont, Félix Guicherd, Robert de Micheaux, Marie-Thérèse et Charles Picard, Monique Toury, Pierre Verlet), d’Allemagne (Ernst Kühnel, Sigrid Müller-Christensen, Wolfgang Fritz Volbach), d’Italie (Gian Piero Bognetti, Tito Broggi), d‘Espagne (Felipa Nino y Mas), de Suisse (Alfred Bühler, Verena Trudel), de Suède (Agnes Geijer) et des Etats-Unis (Claire and René Batigne, Calvin Hathaway, Margaret I. J. Rowe, Edith A. Standen). Travailler ensemble n’était pas une mince affaire à cette époque, car ils avaient tous vécu la Deuxième Guerre Mondiale, et l’antagonisme et la méfiance avaient prédominé pendant des siècles entre certains pays. Mais ces savants décidèrent de prendre un nouveau départ, de surmonter les préjugés anciens et de contribuer à une meilleure compréhension dans leur champ de recherche. Leur but était d’établir une langue définie avec précision pour décrire les éléments techniques et les structures des textiles tissés et de créer une documentation de textiles historiques qui devraient être décrits selon une liste détaillée de questions. Cette documentation, une collection de “dossiers de récensement” pour des textiles individuels, est conservée au musée des Tissus de Lyon où les chercheurs peuvent la consulter.

L’établissement de vocabulaires de terms techniques avec leurs définitions et leurs équivalents en plusieurs langues devait prendre plusieurs années : Les premiers vocabulaires français et italien furent publiés en 1959, l’espagnol suivit en 1963, l’anglais en 1964, le scandinave en 1967, l’allemand en 1971 et le portugais en 1976. Les vocabulaires russess et japonais furent établis encore plus tard. Mais de plus en plus de chercheurs apprenaient à analyser des tissus suivant les méthodes développées à Lyon. Depuis 1956 les Sessions techniques eurent régulièrement lieu à Lyon et amenèrent des générations de chercheurs à aborder les questions liés aux outils, aux structures et aux procédés du tissage de la soie. Encore aujourd’hui, ces cours sont au cœur des activités du CIETA.

Pendant toutes ces années la Chambre de Commerce et d’Industrie de Lyon, propriétaire du musée des Tissus et responsable de son financement, soutenait le CIETA : Le conservateur du musée Robert de Micheaux fut le premier président de l’association (en 1964, il publia un rapport sur les dix premières années de la vie du CIETA que vous trouverez aussi sur ce site web). Dans les premiers temps, son administration ne constitua pas une trop lourde charge, mais le nombre d’adhérents grandit rapidement, jusqu’à dépasser le chiffre de 200 à la fin des années 60, et celui de 300 dans les années 80. Cette situation alourdit les charges de l’administration et la Chambre de Commerce et d’Industrie de Lyon décida de mettre des membres de l’équipe du musée à la disposition au CIETA en tant que Secrétaires généraux, administratifs et techniques. En 1977, Donald King, Conservateur du Département des Textiles au Victoria and Albert Museum à Londres, succéda à Robert de Micheaux comme président du CIETA. Il fut suivi en 1993 par Pierre Arizzoli-Clémentel, Directeur général du Musée et du Domaine du Château de Versailles (et auparavant Conservateur du musée des Tissus à Lyon). En 2009, Birgitt Borkopp-Restle, Professeur en Histoire des Arts Textiles à l’université de Berne (Abegg-Stiftungs-Professur) fut élue en tant que quatrième (et première femme) présidente du CIETA. Elle fut succédée en 2023 par Pamela A. Parmal.

Aujourd’hui, le CIETA compte environ 400 membres, la plupart dans les pays européens et aux Etats-Unis. Ils sont des professionnels de la recherche et de la conservation des textiles, essentiellement des conservateurs de musées, des restaurateurs, des professeurs universitaires et des chercheurs indépendants.

Ils reçoivent des informations sur des expositions, des publications nouvelles, des colloques et des ateliers dans leur domaine de recherche par ce site web. Tous les deux ans, ils re réunissent pour leur Assemblée Générale, leur congrès et un programme d’excursions. Ces réunions, avec leurs discussions, leurs échanges et leurs découvertes ont été au centre des activités du CIETA depuis sa foundation.

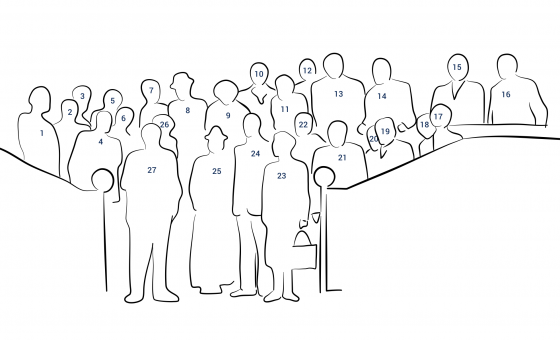

1 – Monique Toury

2 – Interprète espagnol – Spanish interpreter

3 – Dr. Dora Heinz

4 – Dr. Renate Jaques

5 – Dorothy G. Shepherd

6 – Dr. Sigrid Müller-Christensen

7 – Yolande Amic

8 – René Batigne (?)

9 – Felipa Nino y Mas

10 – Claire Batigne

11 – Marie-Thérèse Picard

12 – Pierre Verlet

13 – Charles Lacroix

14 – Félix Guicherd

15 – Prof. Gian Piero Bognetti

16 – Tito Broggi

17 – Edith A. Standen

18 – Dr. Verena Trudel

19 – Robert de Micheaux

20 – Jacques Dupont

21 – Prof. Dr. Ernst Kühnel

22 – Prof. Charles Picard (?)

23 – Agnes Geijer

24 – Calvin S. Hathaway

25 – Margaret I. J. Rowe

26 – Gertrude Townsend

27 – Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Fritz Volbach

Margrethe Hald was a Danish weaver and archaeologist, who in 1950 became the first woman in Denmark to obtain a Dr. phil. in archaeology with a dissertation on Iron Age textiles – despite her having received no previous academic education. Her dissertation was translated into English in 1980 and remains a seminal work for the study of prehistoric textiles. Her background as a weaver gave her a unique insight into the production of textiles, which is evident in her textile analyses and her reproductions of prehistoric dress.

Hald was born in Neder Vrigsted in Eastern Jutland to farmers Rasmus Ole Petersen and Johanne Marie Lauesen. Her father died when she was 3 years old, and she and her three siblings were raised by their mother on the family farm.

Margrethe Hald’s way into academia was an uneven one, and before her first academic publication in 1930, she worked with textiles solely as an artist and craftsperson. She was introduced to weaving through a local weaver, who taught her the basics of the craft. She attended both Askov Højskole, a folk high school known for its weaving workshop, and Tegne- og Kunstindustriskolen for Kvinder (School of Applied Arts for Women) in Copenhagen around the time of the First World War. At the latter school, one of her teachers was Elna Mygdal, a highly skilled textile craftsperson and scholar, who in 1919 became curator at Dansk Folkemuseum (Danish Folk Museum), which in turn became a department under the National Museum of Denmark the following year, where Mygdal was the sole female curator until her retirement in 1936. Mygdal encouraged Hald, who already showed a keen interest in historical textile production, to study the prehistoric textiles at the National Museum of Denmark. These studies culminated in her first academic publication “Brikvævning i danske Oldtidsfund”, an article on tablet-weaving, in 1930. In 1932, she published a popular book on the technique, explaining and teaching it to a wider audience. This would remain emblematic for her efforts to disseminate textile knowledge through various media aimed at the public e.g. appearing in newspapers, magazines and on the radio. Hald’s goal was not just to study ancient textile techniques but to revive and preserve them for future generations.

In 1933-1934, Hald was hired by the National Museum of Denmark to reproduce the Bronze Age dress of the Egtved Girl. This brought her into contact with the Bronze Age specialist H.C. Broholm, and together they published the books Danske Bronzealders Dragter in 1935 (translated in 1940 as Costumes of the Bronze Age in Denmark) and Skrydstrupfundet in 1939. The latter year, she was employed as a permanent assistant at the National Museum of Denmark. Danske Bronzealders Dragter marked the first time that all complete garments of the Bronze Age in Denmark were published and discussed side by side. In 1936, Hald received funding from the Carlsberg Foundation and travelled to London, Vienna, and Berlin in 1936 and 1937 to study Egyptian textiles to compare them to the Danish Bronze Age textiles. Her results were published in Acta Archaeologica in 1946.

Her publications in the 1940s were generally of an ethnographic and folkloristic character, possibly partially caused by the precarious situation in Europe at the time which hindered travelling and international correspondence, but also because she was engaged in writing her doctoral thesis. Her works covered such topics as the nettle as a culture plant, sleeping practices and bedlinen, and laundry.

Margrethe Hald’s doctoral dissertation Olddanske Tekstiler was published in 1950 and an abridged version was published in English as Ancient Danish Textiles in 1980. The dissertation is a comprehensive technical study of Iron Age textiles from Danish bogs and burials combined with ethnographic observations, and it remains a cornerstone in textile archaeology. Hald’s expertise as a craftsperson and artistic capabilities are evident in the many technical drawings accompanying the text, and her broad knowledge of textile production across the world is evident throughout the text. Her findings included the fact that the so-called tubular loom (a warping system for a two or three-beam loom) had been in use in Danish prehistory. This had been a working theory of Hald’s for several years while working with Bronze Age textiles, but it was not until she found intact warp-locks in the material from the Iron Age that she was able to prove its existence at least in the latter period.

The study of the tubular loom would shape much of Hald’s later career, as she travelled to the Middle East (particularly Syria) in 1960 and 1961 to study the still living tradition of weaving Bedouin tents with the technique, as well as to Latin America in 1965-1966, where she documented its existence and use among several tribes.

Despite her impressive career and trailblazing research, Margrethe Hald remained an outsider at the National Museum of Denmark, whether because of her gender or lack of academic education. She did, however, travel a lot and enjoyed a close relationship with several of her international colleagues within her field, such as Grace M. and Elizabeth Crowfoot, Marta Hoffmann, and Agnes Geijer. Together with Hoffmann, Geijer, and Elisabeth Strömberg, Hald wrote and co-edited the first textile technical vocabulary for the Nordic languages, Nordisk Textilteknisk Terminologi (NTT), published in 1967 as one of the CIETA vocabularies. The same year, Hald retired from the National Museum of Denmark but she remained actively engaged in the field until her death – her last publication being an article on the mummy blankets from Paracas published in 1981.

Margrethe Hald’s bibliography is available at: https://ctr.hum.ku.dk/research-programmes-and-projects/previous-programmes-and-projects/the-margrethe-hald-archive-digitalization-and-dissemination/

Her portrait was painted by her brother, the artist Peder Hald.

Morten Grymer-Hansen

Santina Levey, known to her friends as Tina, was an outstanding textile historian and curator and one of the most respected Keepers of Textiles at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, in the 20th century, although her tenure was prematurely curtailed. Her publications on historical embroidery and lace are fundamental to the study of their subjects.

After a history degree at the University of Leeds, Tina took a postgraduate qualification in teaching, her expected career, but was drawn instead to the role of museum curator. Her first significant appointment was as Keeper of Social History for Norwich Museums, and during a fulfilling time in the post she developed her great skill in making both museum collections and the historical and cultural information they embody accessible and illuminating to visitors.

In the late 1960s Tina joined the V & A’s Department of Textiles, where she remained for the next twenty years. The museum had several outstanding textile historians among its curators, including Donald King, Natalie Rothstein and Wendy Hefford. Like all of them, Tina had an encyclopaedic knowledge of European textile techniques, but she developed her own specialism in non-woven textiles, in particular lace and embroidery. Alongside the growing international reputation of her scholarship, she became much admired for her aptitude for the other core aspects of a curator’s role. She strongly upheld the fundamental importance of public service, and was notable in her support for early-career colleagues. In 1981 Tina was appointed Keeper of Textiles, and in 1983 her authoritative work Lace: A History was published. International recognition included her appointment as Vice President of CIETA.

Regarded with huge respect and affection by her colleagues, Tina was undoubtedly one of the V & A’s greatest assets as both curator and scholar. However a radical staff restructuring in 1989 required her, together with other colleagues of Keeper grade, to resign from the Museum. In the following years Tina worked as an independent scholar; she was enormously generous with her knowledge, and much in demand as a consultant. She became a trustee of the Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle, where she was instrumental in securing the donation of the most important private collection of lace in Britain. The gift was celebrated in 2006 in the memorable exhibition Fine and Fashionable: Lace from the Blackborne Collection, jointly curated by Tina and the Bowes’ Keeper of Textiles, Joanna Hashagen.

Tina had for many years been fascinated by the noblewoman Bess of Hardwick (c.1527–1608) and the embroidered furnishings at Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire. In 1998 the National Trust published her book An Elizabethan Inheritance: The Hardwick Hall Textiles, in itself an important and valuable account, but her research continued, culminating in The Embroideries at Hardwick Hall: A Catalogue (2007), which is a benchmark for the comprehensive and authoritative treatment of such a textile collection in all its technical, design, historical and cultural aspects.

Tina never had robust health, and as it declined in her later years her family’s support became increasingly necessary. She was however able to sustain her final major undertaking. A close friend and executor of the leading dress historian Janet Arnold, she collaborated with a devoted team, especially Jenny Tiramani, to secure Janet’s scholarly legacy in the foundation of the School of Historical Dress in London.

A list of Santina Levey’s publications has been published in Textile History, 49:2 (2018), 228-230.

Clare W. Browne

The art historian was born in Gentofte, near Copenhagen (Denmark). In the 1930s she studied art history in Munich and graduated in 1934 with a PhD thesis on “Die männliche Kleidung in der süddeutschen Renaissance” (Male dress in Southern Germany during the Renaissance).

During World War II, artworks were removed from museums and treasuries in many cities and brought to secure places to save them from destruction. In Bamberg (Bavaria) not only were the mantles of King Heinrich II (r. 1002-1024) and his consort Kunigunde moved out of the museum of the cathedral, but the grave of pope Clemens II (d. 1047) was opened and his vestments secured. Fortunately, all objects remained unharmed by the bombings, albeit in a fragile condition. When the decision was formed, after the war, to set up a conservation programme for the treasured textiles, Sigrid Müller-Christensen was entrusted with the task.

A first step was to travel to Sweden where she acquainted herself with current conservation techniques. Upon her return to Munich, a workshop was established, under the administration of the Bayerisches Landesamt für Denkmalpflege and located in the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum (then directed by her husband, Dr. Theodor Müller). In 1949, this meant make-shift arrangements and working conditions that required a fair amount of improvisation, but Sigrid Müller-Christensen and her assistants were committed to their work: “Conservation is a test of character” became the team’s motto. In 1955, the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum presented “Sakrale Gewänder des Mittelalters” (Medieval church vestments), an exhibition and a catalogue that attracted great interest, both from historians and art historians and from a larger audience.

An impressive array of precious vestments (among them the aforementioned objects from Bamberg, the vestments of St. Ulrich from Augsburg, the eagle chasuble from Bressanone, the Alexander mantle from Ottobeuren and the vestments from Regensburg) testified both to the splendor of medieval textile art and to the skills of the conservation team.

Sigrid Müller-Christensen published the results of her studies of the grave vestments of pope Clemens II in a precisely written and carefully illustrated book (Das Grab des Papstes Clemens II. im Dom zu Bamberg, 1960); another important study was dedicated to the textile remains recovered after 1900 from the graves of emperors and bishops in Speyer cathedral (Die Gräber im Königschor, in: Die Kunstdenkmäler in Rheinland-Pfalz, vol. 5, 1972). The impressive list of her publications documents her life-long interest in the textile arts that was not limited to the sumptuous works of the Middle Ages.

For the German-speaking countries, Sigrid Müller-Christensen was a pioneer in the conservation of historic textiles. Based on scientific analyses and historical research, she established techniques that were subsequently developed in other conservation work-shops. A number of younger conservators that she had trained went on to set up and direct the workshops of the Germanisches Nationalmuseum (Nuremberg), the Bayerisches Landesamt für Denkmalpflege (Seehof near Bamberg) the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe (Hamburg), the Deutsches Textilmuseum (Krefeld), and the Abegg-Stiftung (Riggisberg).

Sigrid Müller-Christensen was a founding member of the CIETA; her extensive correspondence (preserved in the archive of the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum) documents her exchange over many years with textile researchers in the European countries and the United States. Charming, enthusiastic and supportive of her colleagues, she was often asked for advice, both on questions of conservation and on technical and historical aspects of medieval textiles. A Festschrift edited by Mechthild Flury-Lemberg and Karen Stolleis (Documenta textilia, 1981) is a monument to the many friendships she formed in her time.

For the long years given to the preservation of Bavaria’s cultural heritage Sigrid Müller-Christensen was awarded the medal “Bene merenti”; she had never held a professional position, but volunteered well into her seventies, when the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum finally established the position of a curator for its textile collections.

Natalie Rothstein’s scholarship in the field of English silks earned her an international reputation as an outstanding textile historian. Her research was carried out during an influential career as a talented and effective museum curator, her cherished profession, spent entirely at the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A), in London. She earned respect for her rigorous integrity, complemented by an engaging high spirit; Natalie had a capacity for inspiring long-lasting friendships with textile colleagues that started out as mutual respect and often matured from cordiality into deep affection.

Natalie Katherine Anne Rothstein was born on 21 June 1930. Apart from a period in Geneva, where her father was attached to the League of Nations, her childhood was spent in London, with education at Camden School for Girls. Her parents were Andrew Rothstein, a left-wing historian and writer, and Edith Lunn, whom he met through the Fabian Society. Both Natalie’s parents had Russian connections, on her mother’s side to a great-grandfather Michael Lunn, born in Lancashire, who became Managing Director of a linen spinning mill and factory at Balashika, outside Moscow. Natalie’s Russian connections were important to her and after her retirement, finding out that the factory was still in production, she travelled to Balashika. There Michael Lunn is still affectionately remembered as a socially responsible English textile entrepreneur and she was celebrated as his eminent descendant.

For her first degree Natalie read Modern History at St Hilda’s College, Oxford, already displaying her commitment to social responsibility as college representative for the university’s Socialist Club. She had decided by her second year at Oxford that she wanted to work in a museum, and after 78 written refusals succeeded in joining the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1952 as a museum assistant, the most junior of the curatorial grades. Initially assigned to the National Art Library, in 1955 she joined the Textile Department, where she was to spend the next 35 years.

Natalie was always glad to have the opportunity to acknowledge the support given to her when she was still a young curator by her V&A colleague Peter Thornton. Then working on research for his own highly influential book Baroque and Rococo Silks (1965), he encouraged her to study the Museum’s collection of eighteenth-century designs for woven silks and in particular to consider the names inscribed on them and to research their place in the English silk industry. This led to her first publication, co-written with Peter Thornton for the Proceedings of the Huguenot Society of London, on The Importance of the Huguenots in the London Silk Industry (1959). It was the first in a substantial legacy of published scholarship she left on the subject of English silks.

In 1961 Natalie completed a research degree (MA) at London University with her thesis The Silk Industry in London 1702–1766, by which time she had become Research Assistant in the Textile Department. But in the previous years she had also had to deal with the diagnosis of lung cancer and major surgery which saved her life but left her with a recurring vulnerability to breathing problems, and an occasional inability to project her distinctive voice. She became a fierce opponent of smoking, and readily made known her views on this.

Natalie was one of a group of remarkable women at the V&A who paved the way for younger female curators to be accepted in what had previously been a largely male domain. She made history at the Museum in 1962 by being the first woman to cross the (then) gulf between Research Assistant and Assistant Keeper. In 1972 she was made Deputy Keeper, and in 1989 her V&A career culminated in appointment as Curator of Textiles and Dress. Natalie’s retirement the following year was marked by an exhibition both expertly curated and quite beautiful: Flowered Silks: a Noble Manufacture of the Eighteenth Century. It was an effective showpiece for her scholarship on the English silk industry, which was published the same year as Silk Designs of the Eighteenth Century in the Collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, with a Complete Catalogue. Several decades after its publication, this remains the standard, authoritative work on the subject.

Her curatorial responsibilities covered a wide range of the V&A’s textile collections, but Natalie considered her particular area of specialism to be woven and printed textiles, their techniques, their history and the progress of their design, concentrating on the period 1600 to 1850 and, within that, on the French and English silk industries. As well as her catalogue of silk designs Natalie published extensively, and also fulfilled an important editorial role for a number of her department’s publications. Barbara Johnson’s Album of Fashions and Fabrics (1987), the facsimile of a fascinating compilation of dress fabrics made by an eighteenth-century Englishwoman, included contextual essays for which Natalie was both editor and principal author. It represents two strands of her major contribution to her chosen subject — her scholarship and her securing of objects of great importance to textile studies for the National Collection. Other notable acquisitions made through her efforts (both research-related and fund-raising) were the three volumes of silk designs by Anna Maria Garthwaite dating from 1743 and 1744, which surfaced, previously unknown, in 1971, and the highly important group of pattern books of Spitalfields silks, together with designs, point papers and production ledgers, sold at the dispersal of part of the Warner Archive in 1972.

Natalie’s research on the English silk industry included significant work on the transatlantic textile connection and the American colonies as a market for English goods. This is an area of research for which colleagues working on American collections became particularly grateful, and she was highly regarded for her work internationally as well as in Britain. International collaboration was very important to her. She had joined CIETA in 1956, immediately after having participated in the very first technical course, held by M. Félix Guicherd, and remained an active and enthusiastic member for 43 years.

In her later years at the V&A Natalie necessarily became increasingly preoccupied with administrative concerns. Relieved of these on her retirement from the Museum, she enjoyed returning to the rewarding discipline of cataloguing textile collections and undertook this for a number of institutions, including the Museum of London and the Museum of Costume in Bath, the National Trust, and museums in the Netherlands and Sweden. A particularly stimulating collaboration was with the Abegg-Stiftung in Switzerland, for which she curated an exhibition of eighteenth-century English silks in 1998 and contributed to the related colloquium as key-note speaker. Invited to suggest other speakers, she enlisted contributions from a cross-section of textiles and fashion curators from Britain, Europe and America. Among these were a number of younger colleagues happy to acknowledge their debt to her for the standards of scholarship she set and in particular through her generous support and encouragement to them earlier in their careers.

Everyone who spent any time with Natalie quickly became aware of her distinctive character. Sharp-minded and determined, she could be a dogged opponent, particularly when in her perception an injustice was being done and she refused to do anything simply to court popularity. But this was allied to a great generosity and innate sense of morality, together with good humour and an entirely practical attitude towards dealing with whatever needed to be done.

A first version of this text and the list of publications was published in Textile History, 41:2 (2010), 236-240.

Clare W. Browne